Investorship

Spending Your Way to Wealth(s)

Chapter Two — The Problem With Normal

This book is available at no cost to financial literacy educators everywhere. Here is the second chapter, explaining why our normal responses can be wrong. (Later in the book, we explore how this normal-but-wrong response applies to spending and wealth.) A secure PDF version of the full book is available at no cost, using the link below. Please contact us for information on obtaining free copies of the printed version for your use.

Chapter 2

The Problem with Normal

“We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

— Walt Kelly’s Pogo

When it comes to spending and investment, we will see that we’re all normal, that we make normal mistakes, usually without thinking, and that we can change our unconscious spending behavior to achieve actual wealth. But before we can do this, we need to understand what normal means.

Normal is not the same as average—the statistician’s way to lop off all the interesting differences that make us human. Normal means much more. In the world of flesh-and-blood human beings, no one is average, but most of us are normal. In a nutshell, the basic thoughts and actions that are common to our species—despite our infinite differences—are what make us normal. It does not protect us from folly, but most of us are there.

A key aspect of being normal is the fact that we do things for valid, predictable reasons. The principal one of these is to survive. Our innate desire to continue living, preferably without discomfort or trauma, drives us to find ways to meet our needs. Mere survival is not all. We also want to thrive and to satisfy our many needs and wants. This makes things complicated.

Being Normal Doesn’t Mean Being Right

Frank Capra’s classic film, It’s A Wonderful Life, is a celebration of ordinary, quirky people leading outwardly ordinary lives. The setting is commonplace—apart from a visiting angel and an alternate version of history, of course. The characters are remarkably normal. We identify with them. They live and behave in normal ways, as most of us do.

But the movie’s famous bank run scene shows how problematic normal can be. Ordinary people, sparked by news of the market crash and frightened by sirens and general chaos, descend on the Building & Loan to demand their money. The movie’s hero begs them to think about what’s really happening. He persuades them—barely—to reconsider their first impulse, and disaster is averted. As in real life, the most common, instinctive reaction of people to a crisis can be both perfectly normal and dead wrong.

We’ve all been there. An ordinary, routine situation changes unexpectedly. We automatically do the first thing that pops into our minds and, without knowing exactly what happened, we find ourselves in a ditch—sometimes a literal one. It happens without warning: driving to the store, speaking at a staff meeting, going on vacation, or trying to fix the sink. (Helpful hint: Turn off the water first.) Things were going so smoothly, events turn unexpectedly wrong, and our first, gut reaction has a really good chance of making things worse.

During World War II, American GIs invented a saying for this: SNAFU (Situation Normal, All Fouled Up).

The Basics of Bias

To understand why this happens, we must acknowledge an important fact of life: Everyone is biased. They are a natural and normal part of who we are. Often, however, the word bias conjures negative emotions, as in the case of unjust racial or gender-related discrimination. However, bias, in the broadest sense is simply our preference or inclination for or against something. It can be conscious or unconscious, positive or negative, subtle or obvious.

A bias is an information-processing shortcut, an inference or assumption based on previous experience that allows us to make decisions, rightly or wrongly, in an overwhelming sea of information. A completely unbiased human would not be able to function. They would waste vast amounts of time and energy trying to experience, analyze, and develop a response to everything.

Biases come from a combination of factors. One is our ability to remember, which is limited, and the need to sort, discard, and simplify information. Of necessity, we discard specifics and form generalities. We reduce events to their key elements. We edit and reinforce memories after the fact. We are also drawn to details that confirm our existing beliefs.

Bias also arises when we fail to understand the deeper meaning of our environment. We tend to simplify and see stories and patterns even when looking at incomplete data. We also feel the need to act quickly. To get things done, we focus on what we’ve already invested our time and energy in. We also favor simple-looking options over complex or ambiguous ones.

The list of normal, human biases is long. As discussed later in this book, many of them unconsciously influence our decisions when it comes to spending and wealth. For example, the Complexity Bias describes our tendency to give undue credence to complex concepts. Faced with two different choices over, let’s say, investment strategy, it is perfectly normal for us to prefer a complex approach over a simple one. It just feels right, even when it’s not. As we will see in Chapter 8, elaborate strategies based on regular buying and selling of individual stocks consistently produce results that are inferior to a simple approach, such as contributing regular amounts to an S&P 500 index fund and/or a Target Date fund—as outlined in Appendix A.

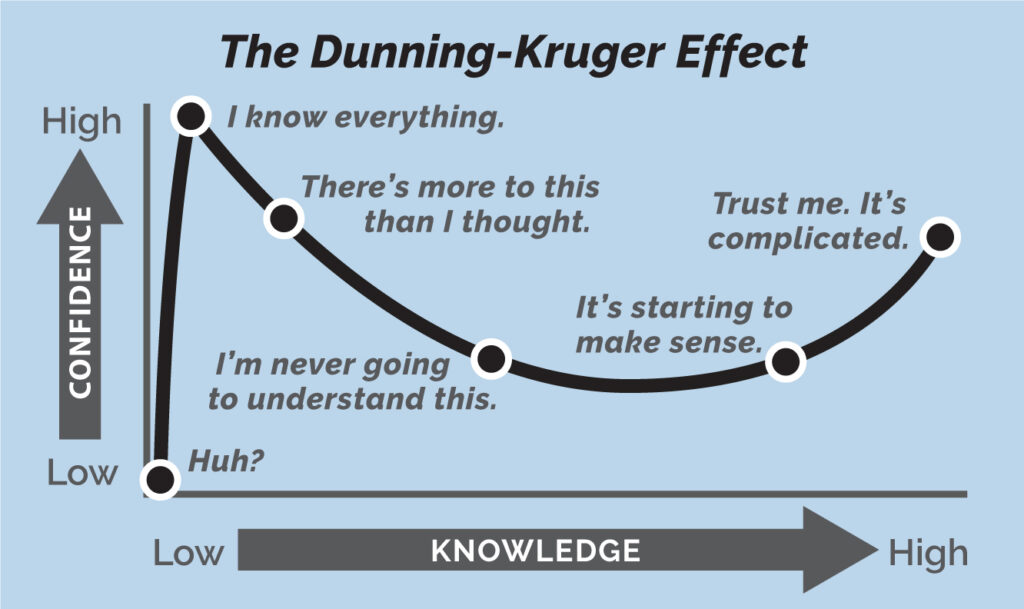

One such bias is the unwarranted confidence of beginners, known as the “Dunning Kruger Effect.” This explains why new drivers have more accidents—and pay higher insurance premiums. It also explains why first-time investors tend to do more poorly than experienced ones. Such investors feel that they understand the basics and are prone to making inaccurate assumptions and incorrect decisions.

CAUTION: A small amount of knowledge may manifest itself in an unwarranted level of confidence, leading to inaccurate assumptions and incorrect answers.

Am I Biased?

The first step towards understanding these normal, human biases is to discover that we have them. We take unconscious mental shortcuts—because we are human—but we tend not to think of them as biases. Take some time to consider your own responses to everyday situations. For example, are there certain kinds of music or art that you either love or hate? That is a cultural bias. Do you prefer or dislike certain types of food, fashion, or entertainment? Do you have strong, “gut feelings” about pets, people of your own generation or another, or about your own family members? Each of these preferences or dislikes is something you experience with little conscious thought. In other words, it is a bias.

Some biases, particularly racial- or gender-related ones, are harmful and unjust. However, in many cases, a bias is neither right nor wrong. It’s simply a personal preference put on autopilot. In any case, it is worth knowing that we have them. If a bias makes us prone to bad decisions, then it’s time to reexamine and adjust them.

The problem is that our naturally occurring and completely normal human bias can lead us to a decision with harmful consequences. When a situation changes from our past experience, or if our bias was originally based on faulty or incomplete information, we follow our programming, so to speak, and experience poor results. Eventually, bad results may force us to confront a particular bias and change it, but humans can be a stubborn lot when it comes to change.

Financial bias (the subject of this book) is less obvious than those listed above. However, financial bias does follow the same pattern as the others and can lead to either good or bad results.

One thing is certain. Our preconceptions and mental shortcuts regarding spending and wealth are evidence that each of us is normal.

Reactive (System 1) and Reflective (System 2)

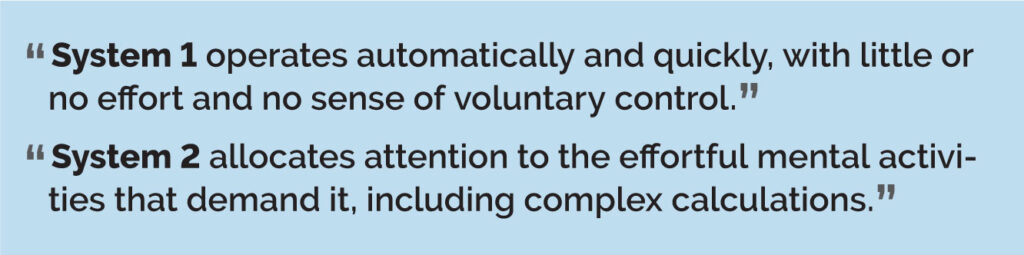

We meet our many needs and wants by making decisions and acting on them. Some of these decisions are unconscious and intuitive in nature, seemingly made automatically and without effort. Others are more deliberate and reasoned—the result of a conscious thought process. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman refers to these two modes of thinking by the labels System 1 and System 2 widely used by many psychologists.

In this book, we will also refer to them as Reactive or Reflective responses to a situation—like a scary dip in a stock market average.

Both of these modes are valid, very human responses. Intrinsically, they are neither right nor wrong. They are simply the ways we cope with incoming stimulus. When we first see the face of someone weeping, our negative, Reactive interpretation is largely automatic and subliminal (System 1). She is sad, we suppose. Then, after learning the context, our Reflective (System 2) abilities realize that the person was celebrating a one-point win in a basketball game. Our initial reaction was perfectly normal, but wrong.

When we see a written math problem, we recognize it as such, but most of us are unlikely to unconsciously or intuitively (System 1) come up with the answer. If we try, we are likely to get it wrong, as was the case with the ball-and-bat question in Chapter 1. To get the right answer, most of us would engage more deliberately (System 2) and work out the problem with paper and pencil.

Because we’ll be referencing Kahneman’s thesis throughout this book, it may be helpful to quote his definitions. You are encouraged to bookmark this page or highlight the definitions.

The Reactive mode of thinking is an ingrained part of our species’ history of survival. Eons ago, reacting instantly to the presence of a large predator was literally a life-saving response. It became a characteristic that our uneaten ancestors passed down to us.

Our ability to do this serves us well today. Our Reactive, System 1 brains let us put routine matters on auto-pilot, so to speak, and conserve our limited Reflective, System 2 responses. No longer a pure survival mechanism, our habit patterns help us cope with our ever more complicated lives.

Just for fun, think of the things you do every day without a lot of conscious thought. They range from the mundane, like using a knife and fork or tying your shoes, to the more specialized, like using a computer or mobile device at work. When you first learned to do them, it required a lot of conscious, Reflective energy. After they became routine, it required much less.

Driving to the Store

As an experiment, try to recall the specific actions you took the last time your drove to a grocery store. Unless something extraordinary happened on the way, there will be many blanks. You arrived at your destination with little memory of what turns you made, how you maintained a safe distance from other cars, whether you obeyed traffic rules, or even what you saw or heard on the way.

Routine driving is an example of Reactive behavior. It is cognitively easy. It requires only nominal conscious effort. You mind is free for other things, like listening to music or conversing casually with a fellow passenger.

The routine act of driving is behaviorally automatic. But if something out of the ordinary happens on the road ahead, then your conscious, Reflective brain re-engages to deal with the new situation. Conversations and other actions unrelated to driving cease.

This wasn’t the case when you learned how to drive. Your conscious, Reflective process was fully active as you learned to steer, use the pedals, enter traffic, and parallel park. In fact, you were probably too conscious during the learning process, making mistakes like over-steering or braking too suddenly. But gradually, and with plenty of practice (and an instructor or companion with patience and courage), you developed the intuitive habits that embody being a good driver. You transferred a set of learned, Reflective behaviors to a set of semi-automatic, Reactive behaviors.

The System Shift and the Lazy Controller

Let’s start by recognizing that we all tend to be lazy at times. It’s part of our evolutionary heritage—to assure that we have sufficient energy to run from dangerous situations, like the approach of a man-eating beast. It’s not a pejorative or degrading term, it’s merely a statement of fact. It also helps explain why we delegate many actions to our Reactive brains. So long as these activities remain routine and predictable, they require little expenditure of energy and we do them without much thinking, and usually do them well. But as soon as there is a change in the environment, our once-automatic activity changes.

Try another experiment. While walking and chatting casually with a friend, bring up a serious topic and observe what happens. Invariably, she or he will slow down. (If you’re really friends, you’ll slow down too.) Kahneman posed a similar experiment. He asked a walking companion to compute 23 times 78 in his head. The friend stopped in his tracks. He shifted away from a routine Reactive activity to focus on a more demanding process.

Like physical exertion, conscious, Reflective activity requires effort. Because our normal tendency is to conserve finite mental and emotional resources, we are prone to take the path of least resistance. Letting our unconscious, Reactive brain take over—responding intuitively and impulsively—is all too common, especially when we are stressed or tired or mentally exhausted. We have what Kahneman refers to as a Lazy Controller. That’s not an insult, just a natural, self-protective part of being human. We focus on what we perceive as the single, most important thing. Out of necessity, we delegate seemingly less immediate or important tasks to our Reactive, System 1 nature.

The Hazards of Being Normal

Acting intuitively and spontaneously is not a bad thing. It can be remarkably successful. A well-trained athlete, artist, or mathematician spends less energy performing complex tasks in his or her area of expertise than they did while learning to do it. It appears effortless and natural. But some have suggested that intuition alone—the ability to think without thinking—is an intrinsically superior mode of thinking. It is not.

Of course, part of us wants to believe that intuition is superior. Things that are more familiar or easier to figure out seem truer than things that are novel, difficult to see, or require hard thought. (As we’ll see, that’s an example of a type of thinking error called “cognitive ease.” See Appendix E.)

The problem is, our intuition may not be founded in fact or in deliberately cultivated habits, but in presuppositions, cognitive illusions, and biases. Our response may seem natural, even easy, but it can be wrong, and lead to bad or at least ineffective results. It results in a situation that is totally normal, but all fouled up.

The most common way our intuitive, Reactive habits lead us astray is when an environment is different from the one to which we are accustomed. What was “normal-smart” in one situation can become “normal-stupid” in another. As we will see, when allowed to occur in the realm of spending, “normal-stupid” can have disastrous financial consequences.

Looking Both Ways

In North America and most European and Asian countries, vehicles travel on the right side of the road. As a result, pedestrians crossing the road habitually look left first, before looking right and then left again. Most of us do this without thinking—for good reason: the potential hazard from oncoming traffic is more immediate to a pedestrian’s left, because cars use the right side.

But in the United Kingdom and Australia, the opposite is true. Vehicles use the left side of the road, and pedestrians look right first before crossing. Two different groups of people have developed Reactive coping habits which are literally 180 degrees apart.

An American who travels to London has exactly the wrong instinct when about to cross a busy street. The likelihood of unintended mayhem was not good for tourism. So, at many London pedestrian crossings, you will see—in large letters—the words “LOOK RIGHT.” It’s an attempt to adjust an unconscious but potentially fatal habit.

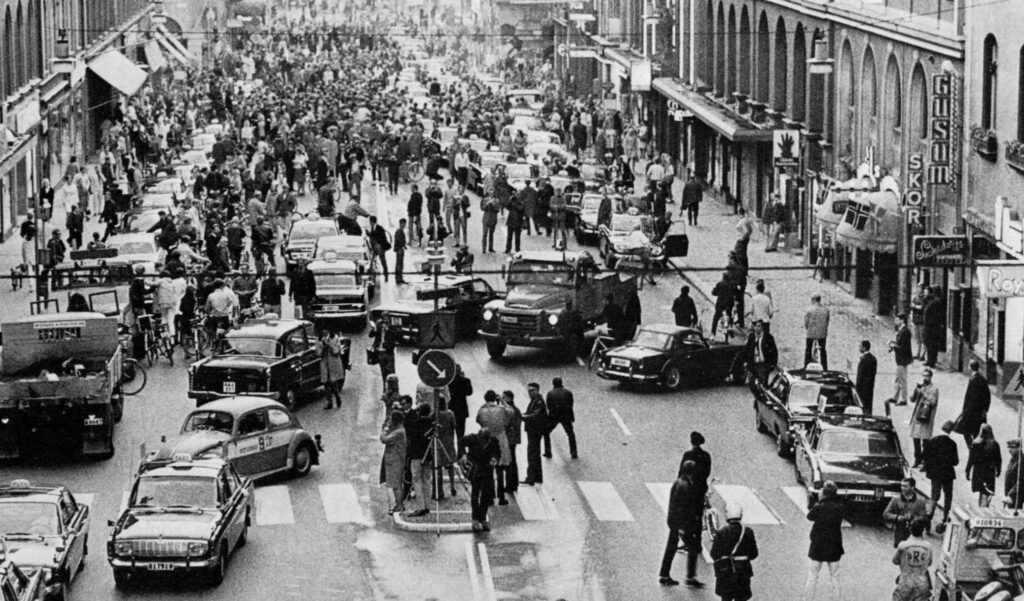

Changing habits to cope with new situations is difficult but not impossible. When Sweden switched from left-side to right-side driving in 1967, temporary chaos ensued—despite months of planning and public announcements. Change is possible, however. With practice and patience, people can unlearn a potentially harmful response and learn a different one. In Sweden today, a pedestrian’s instincts are the same as those in America—but both must use caution when in the U.K. or Australia.

Switching from driving on one side of the road to another can be chaotic. (Stockholm on September 3, 1967. Photo by JanCollsiöö – Så var det, Public Domain)

There are also ingrained habits for which the negative consequences are vague or unknown—giving you no reason to change them. Think about some things you do automatically that have no actual results. Have you ever done any of the following:

Checked your email within five minutes of checking it the last time?

Pressed the button repeatedly when summoning an elevator?

Pushed on a door when the sign reads “pull”?

An automatic response can be both perfectly normal and wrong at the same time. Our Reactive habits also make us bad guessers. As proof, if you haven’t done so already, answer the five questions at the beginning of Chapter 1.

Making Things Worse

Our tendency to do things Reactively is more pronounced, and more likely to have unfortunate consequences, when we feel a sense of urgency. As our lives becomes more hectic and complex, we have less time to pause and consider things Reflectively. According to the Association for Psychological Science, when people under stress are making a difficult decision, they tend to pay more attention to the potential upside and less to the downside. They also find it more difficult to control their urges. Getting immediate relief becomes more important than the potentially negative consequences.

Decisions made in response to urgent, immediate stimulus carry a greater risk when it comes to spending and investing. (In Chapter 8, we will discuss how all the “noise” can increase our sense of perceived urgency, preventing us from making conscious, Reflective decisions.)

While there is no panacea for making our lives simpler, it is important to recognize that part of being normal is making decisions under less-than-ideal circumstances. To help activate your Reflective nature, begin by asking, “Is this really urgent or does it only feel urgent?”

Resistance to Change

Changing our Reactive behavior is no small task. As natural conservers of our own energy, we resist change as a matter of course. If the positive incentive for changing our behavior is too small—or unknown—then we ignore the results and continue doing the same thing. If the negative consequences are remote or seemingly insignificant, then the same thing happens—nothing. But sometimes, our resistance to change entails unnecessary risk.

Fasten Your Seat Belts!

First developed for automobiles in the 1950s, seat belts have a scientifically proven benefit: Your chance of death or injury is far lower if you wear them. Convincing motorists to use them is another matter. Since their introduction, and despite increasingly strict “click-it or ticket” laws, some motorists resist, especially when the trip is “only a few blocks to the store.”

The problem? Our normal, Reactive brains see the present (where accidents are statistically rare) as more real than the consequences of an accident that has not yet happened. We unconsciously discount risk and resist an inconvenient change in behavior.

Automakers’ earlier, psychological solutions had mixed results. If seat belts were not used, an annoying beep or tone sounded immediately and continuously. It did not stop until the seat belts were fastened. However, users would sometimes fasten the seat belts permanently and sit on them—or disable the warning system altogether.

As a better solution, car makers created a seatbelt warning that emitted intermittent audio sounds. The first chimes or tones were a gentle reminder, followed by a pause, and then a series of increasingly loud and strident beeps. The annoyance factor grew, not so rapidly that the user was motivated to disable the warning system. It was just annoying enough to make wearing seat belts the lesser of two evils. Over time, the act of fastening one’s seatbelt becomes automatic.

Seatbelt use is not yet universal, of course. But with a combination of strict laws and more subtle warning systems, it is becoming more common. The acknowledged benefit (living) is supported by a Reactive, System 1 habit.

Let’s go back to an example cited earlier: checking your email (or Twitter feed or Facebook posts) every few minutes. There is increasing evidence that doing so out of habit is extremely costly—sapping our productivity. According to a 2008 University of California Irvine study , “The cost of interrupted work: more speed and stress,” it can take an average of over 23 minutes to return one’s focused attention to a task after being interrupted. The more engaging the interruption, the harder it is to switch back.

However, merely knowing about that long-term cost does not automatically equip us to cease our Reactive habits. We are resistant to change when given the choice of easy versus difficult. It’s perfectly normal to drop everything and look, even when we know the email will be mostly spam and the posts filled with distracting nonsense. The act of checking creates an emotional reward—seemingly meeting the need for connection. The negative consequences are less clear, and the Reflective effort (not looking) more daunting.

The Roundabout Riddle

More common in Europe, well-designed traffic circles or roundabouts are slowly gaining acceptance in North America. They are demonstrably more efficient, compared with traffic-lighted or four-way stop intersections. However, public resistance to roundabouts is a good example of normal, unconscious, Reactive bias.

When roundabouts are first proposed in a community, the most common objection is that people aren’t used to them, which they believe will result in more accidents. They don’t feel the same as a four-way stop, so we resist the idea of learning new habits.

What overcomes our unconscious bias is experience. We learn subtle visual cues, like the direction of the other car’s front tires. Gradually, our habits change, and our confidence grows.

Just for fun, consider your own biases on the subject of roundabouts. If such intersections are rare or nonexistent where you live, what is your first, gut reaction to them? If they already have been implemented, what’s your attitude?

Practice and Patience

Despite our innate resistance to change, it is entirely possible to adjust our habit behavior from “normal-stupid” to “normal-smart.” In his excellent book, The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg notes that “changes are accomplished because people examine the cues, cravings, and rewards that drive their behaviors and then find ways to replace their self-destructive routines with healthier alternatives.” Such change is more likely when we believe change is possible—something that is more likely in a group context than when we go it alone.

So, in the case of constantly checking email or social media, knowing the reward of doing so less often (being more productive) is only one step. The other is recognizing the craving (the need to connect) and substituting a different activity, such as regularly connecting with actual humans, in order to meet the need.

The roundabout illustration given earlier is an imperfect example of changing our Reactive, System 1 biases, because the change—to a more efficient system—is not an individual choice but a government-mandated one. However, it is a good illustration of how our biases can in fact have less than ideal results. What seems intuitively right is actually preventing long-term success, both in getting to your literal destination (traffic) and your financial one (spending). Our natural response to financial stimulus, like the craving for a new car or the gut reaction to a short-term stock drop, will often put us in a metaphorical traffic jam. A familiar-seeming situation is not what it appears to be, so your instincts result in poor outcomes.

Change is possible, however. The first step is to recognize that our Reactive habits are completely normal—a part of our energy-conserving nature, if not our literal survival. They are also prone to numerous biases and thinking errors. The next step is to know the full extent of what our automatic, Reactive response actually costs, not only in the distant future but also in the present. We also need to be constantly reminded—as with the intermittent seatbelt warning—that a different action is possible. Perhaps the most important factor is our belief that a different behavior, reinforced by a group of positive, change-minded peers, will satisfy the basic need in a far more satisfying manner. With practice and patience—and the support of others—we will discover that once-unfamiliar habits can help us reach our goal.